Chapter 11: A growing map

Time elapsed: 12y

It didn't take long for this part of the world to become connected again. Every new telegraph tower reduces message travel time from half a day to just a few minutes, and once distant locations are now starting to feel like a part of your own backyard.

It is certainly quite the experience to now be in regular contact with the city of Redmont across the bay. You and its mayor have become quite close, despite having never met each other! It truly is remarkable.

The telegraph service is being used more and more as time goes on. People are even able to request information that your team finds in the database and sends back.

This is usually a good thing. But you did hear one disturbing report lately from Landevin who had just returned from a trip across the great mountains to the east.

Landevin visited two cities there called Bulton and Emond's Field that have been at war for years. As Bulton is closer to your telegraph route, its people have been crossing the mountains to use it. Their data requests were pretty bland: information about chemicals and metal and manufacturing and so on. But they used it to gain an advantage in the war. And what's more, they had been doing this for years already! By the time you found out about it, they had already won.

Hopefully they were the good guys...

What else are people using it for that you are unaware of?

Well, there is no stopping progress now. Speaking of which, it's time to get back to the map service you are putting together to make travel easier for the average citizen.

The map service and dataset

In this chapter we can reveal something that you may have already figured out yourself: the town of Toria where Aeon lives is located at the same spot as the city of Victoria, British Columbia in modern-day Canada! The population of the world has dropped by quite a bit since then, and many names have changed. The secret has been now been revealed because in this chapter we will be dealing with so many pieces of location data that it is now obvious what part of the world we are looking at.

The world felt like a very large place in the distant past, and the same goes for the people of Aeon's time. Take the distance between Toria and Bulton, known as Victoria and Calgary in our time, as an example. If you ask Google Maps or a similar service how long it takes to walk from one to the other, the answer is about 270 hours. But this is assuming the infrastructure of the modern day such as paved roads and ferries to cross the water. Things are different in Aeon's time. Boats are less common, roads are less developed, the entire Rocky Mountains has to be crossed first, and safety is not guaranteed either. Such a journey could have taken a month or longer.

It's no wonder that cities simply lost contact with each other over the centuries between the present day and Aeon's time.

But as the telegraph system continues to grow, people are becoming aware of locations that they handly knew anything about before. A message can now be passed from Toria to the town of Revelry at the end of the telegraph line within half an hour. Any news from Bulton only has to cross the mountains and reach Revelry for Aeon to be aware of it.

The most fortunate thing for Aeon's team is that the library inside the tunnel contains information on these locations, including their exact coordinates. So instead of having to come up with a system to measure the coordinates themselves, all they need to do is find out which city matches which city in the past.

As a result, Aeon has been able to put together a basic dataset for all of the locations nearby as well as two of the cities across the mountains. You can see the raw data for the towns inside this dataset which adds them inside a single INSERT statement. The location data is precise, making it easy to put it into the geo functions that we learned in the last chapter. Let's give two of them a try!

This will be a big help, because common people during medieval times generally traveled using something known as an itinerary: a set of places that you needed to travel to get from one point to another.

Here is part of one called Liber Addimentorum from the 13th century to give you an idea of what they looked like.

A person with an itinerary in hand would then go to the first destination, ask the locals which road to take to reach the next destination, and so on until the final destination is reached. An itinerary is more of a list of places to go than an actual map. If you are curious about the subject, check out this video which explains the experience for the medieval traveler.

But with the precise location data in Aeon's database, people will now be able to construct their own maps instead. Let's use our knowledge from the last few chapters to do so.

We'll start with a few define statements for the fields of our town records to make sure that the data is as we expect.

Each town will be connected to one or more towns by some sort of route. We can use a RELATE statement for this. We'll just call this graph table to. Since we know that a town will always have a location, we can use this to calculate the bearing inside the table to.

Unlike the other RELATE statements we have used so far, it's fine to relate Town 1 to Town 2, followed by Town 2 to Town 1.

This is okay because going from town:one to town:two isn't necessarily the same as going from town:two to town:one. You might have a gentle downward slope the whole way, while going back will be all uphill and more tiring. Or maybe town:two has stricter border controls than town:one, so you might want to add a note about that and how best to bribe the guards to get in. This information won't be needed for the route to town:one.

Each to relation should be unique though, to make sure that we can't type RELATE town:one->to->town:two more than once. We can do this with the DEFINE INDEX...UNIQUE technique we learned in Chapter 8, except that it's a bit simpler this time. Instead of needing to create a separate key field composed of the sorted in and out fields, we can just define the index on the in and out fields together. This will make a single index composed of the two fields.

With this index set up, we can relate one town to another via to, and from the other direction from the second town to the first, but no more.

Next, we should add some fields to the to table to describe the route. Aeon and the team have the exact location data for these towns, but no precise information on what the routes are like connecting them. As a result, their only choice is to send messages to these locations to ask how the road is to the next location. Questions like "How straight is it?" and "Is there a road? Is it by land, or over water?" are about as good as things can get at this point.

Literal types

To represent the state of a route from one destination to another, we'll make a few string fields that have to be of a certain value. The options we will allow are as follows:

A route can be: "straight", "crooked", or "very crooked".

Terrain can be: "road", "normal" (not a road, but not too hard), "hard", and finally "water".

Slope will be of four types: "flat", "up", "down", and "steep". We don't need "steep up" and "steep down", because a very steep slope is difficult to travel to matter whether you are going up or down it. A steep slope is no fun no matter which direction you are going.

So if a local from The Naimo tells Aeon that "Yep, there's a real nice straight road going to The Hill, no complaints", it can be turned into this object that can be used to make a to graph table.

And if another local from Black Bay complains about all the islands that get in the way when crossing the sea to Gaston, then this object can be used to represent the trip.

One way we could define these fields is by adding an assertion that the $value of the field is contained within a number of values that we have decided are valid. The definitions in this case would look like this:

But there is another type that we can use that is a bit simpler: the literal type that we first used in chapters 5 to 8. In those chapters we defined a literal on a single field, but a literal can be used in regular queries as well. For example, you can even make a literal of type "Aeon"! It can have the value "Aeon", nothing else.

The first query will work, but the second doesn't quite match so SurrealDB will return an error.

We can put a | between all possible values in the same way that we did with our previous schema too.

A literal can include type names too (string, number, duration, etc.), as well as arrays and objects. This next literal can be one of three things:

a string equal to "Uninhabited",

an object with a

typefield equal to "city" and apopulationthat is an integer,an object with a

typefield equal to "town" and apopulationthat is an integer.

A literal is pretty similar to an enum or a union in a lot of programming languages.

Our literal types for the table to will be pretty simple, just a list of possible string values. All together they look like this.

Entering the data

With our first definitions done, let's get to the raw town data and the raw trip data compiled by Aeon and the team. We now need to use this raw data together with the fields we have defined.

The town data looks like this:

And the trip data looks like this.

After inserting the data, we can put them all together by using a FOR loop on all of the trips to start a RELATE statement. First we will use a SELECT along with ONLY and LIMIT 1 to let SurrealDB know to return a single object instead of an array.

Then we will start the RELATION statement:

And then SET some values for convenience.

The first three are pretty straightforward:

Then calculate the distance:

Next is something we will call speed_modifier. The default speed for a trip will be 1.0, while road conditions can increase this modifier (which is good) or decrease it (which is bad).

To represent this, we can follow a pretty simple IF ELSE pattern.

As a result, a person could have a speed modifier of up to 1.44 when traveling on a road on a gentle downward slope (1.2 1.2), and as low as 0.175 when traveling on a path that is very crooked, steep, and in difficult terrain (0.5 0.5 * 0.7).

Finally, we will add a days_travel field. This assumes that people will move at a default of 20 km per day on land. Water is slightly more complicated. It is faster (100 km per day), but assumes an extra day to find a boat in the first place. The speed modifier for water will only involve crookedness, because water can't have a slope. Any other conditions have to do with weather, which can't be put into a database ahead of time.

Putting all of this together gives us a complete dataset for these few towns. You can copy and paste the dataset into Surrealist and then take a look at the results for yourself! Let's take a look at the places that you can get to from Toria:

If you change 'Toria' to 'Gaston' (today's Vancouver), you can see that there are two places to go: one to the town of Abeston to the east, and another across the water.

Wait a second, both of these routes go to the east. What about the route that goes south into the modern-day United States?

Oops! Looks like we forgot to add Redmont (modern day Seattle). The trip between these two cities is pretty easy and just involves walking south along the coast a bit. People in Aeon's day will have an easy time traveling between the two locations as well.

We could accomplish this in a few ways:

Modify the dataset, restart the sandbox environment, and paste it back in to run. This is easiest for us at the moment, but for Aeon and the team this would not be ideal because they are using persistent data and don't want to delete records if they don't have to.

Copy and paste the whole RELATE statement and modify it to include the trip from Gaston to Redmont. This works fine but takes a bit of typing...and we might find later on that we need to add another RELATE statement.

Define a function to automate the process. Once a function is defined, we will only have to pass in a few parameters and that will be the end of the task.

So let's learn how to do that!

Definining functions

Not only does SurrealDB come with a large set of functions to pick and choose from, but also lets you define your own. To start defining your own function, just type DEFINE FUNCTION and the name of the function, which starts with fn::. After this you need to add parentheses to hold the arguments, then braces (curly brackets) to hold the function body, and finally a semicolon to finish the statement.

Putting that all together, a function without any arguments will look like this:

This function only returns an empty value at the moment, but it still works!

Our function should take the arguments that we have been using in our objects to construct the to tables. Note that even at this point there is some type safety involved, and the function can no longer be called without providing all five arguments.

The body of the function is not a challenge, as all we have to do is copy and paste the content we already have and modify a few parameter names. In addition, we can have the function return the relation that was successfully created instead of just returning NONE. To do this, we can assign the RELATE statement to a parameter, and return a message at the end of the function to let the user know that the new trip has been added.

And now the function will work!

Can we make the function a little bit more rigorous though? What if we enter a town that isn't in the database, or put the parameters in the wrong order, or something else?

Indeed we can. One way is to use a keyword called THROW, which stops the execution of a query and returns an error instead. Here is a simple example of a dividing function that first checks to see if the second number is zero. SurrealDB already checks to see if a user tries to divide by zero (it returns NaN, which stands for "Not a Number"), but by using THROW we can make the error message a little more personal.

Since this function returns a value, we can make it extra rigorous by adding -> number to instruct SurrealDB that this function must return a number, and nothing else. Adding a return value also improves readability for anyone reading your code, because now you don't need to read through the function to know what value will be returned.

The output shows that the first attempt to use fn::divide did indeed stop at THROW:

We can now use THROW for the fn::add_trip function, which will now make four checks along the way to ensure that the parameters are correct. The first two checks are to make sure that both $crookedness and $terrain are valid input, as there is no reason to continue at this point if they are not. If these two pass, then the function will query for the town at $begin and the town at $end. It will then check to see if either of the towns do not exist, by using the count function to see if the length is zero. If either of these cases is true, then we don't have two towns that can be related, and THROW is used again to stop executing the function.

And since the function returns a string, we can add -> string as its signature to make its output clear.

Some experimenting with the function shows that it is now a lot stricter than before. Here is the output when none of the arguments are correct:

And when only one of the arguments is correct:

Output when one town exists but the other does not:

And finally a case where we have managed to satisfy the add_trip function by adding the second town.

These two made-up towns are just a few hours' distance from each other, though it takes you a bit longer when the slope is uphill.

If you prefer SurrealDB's literal type style, you could even remove a few THROW statements by instead having the function take an object in which the possible values are already defined. In this case, the function will take a single object called $input that holds all of the necessary fields and possible values.

Which input format to choose depends on your preference. With a literal type the possible input is evaluated even before the function is called. On the other hand, the error output is no longer customised. As a rule of thumb, THROW is better if you want to choose your own error output while a literal type is better if you prefer showing all the possible values up front - such as for an API for others to use that will only show the function signature. In that case, you don't need to show any of the function's internal code to explain how it should be used.

In any case, with the new towns added, people can now use the information from queries like this that Aeon or the team will put together for them.

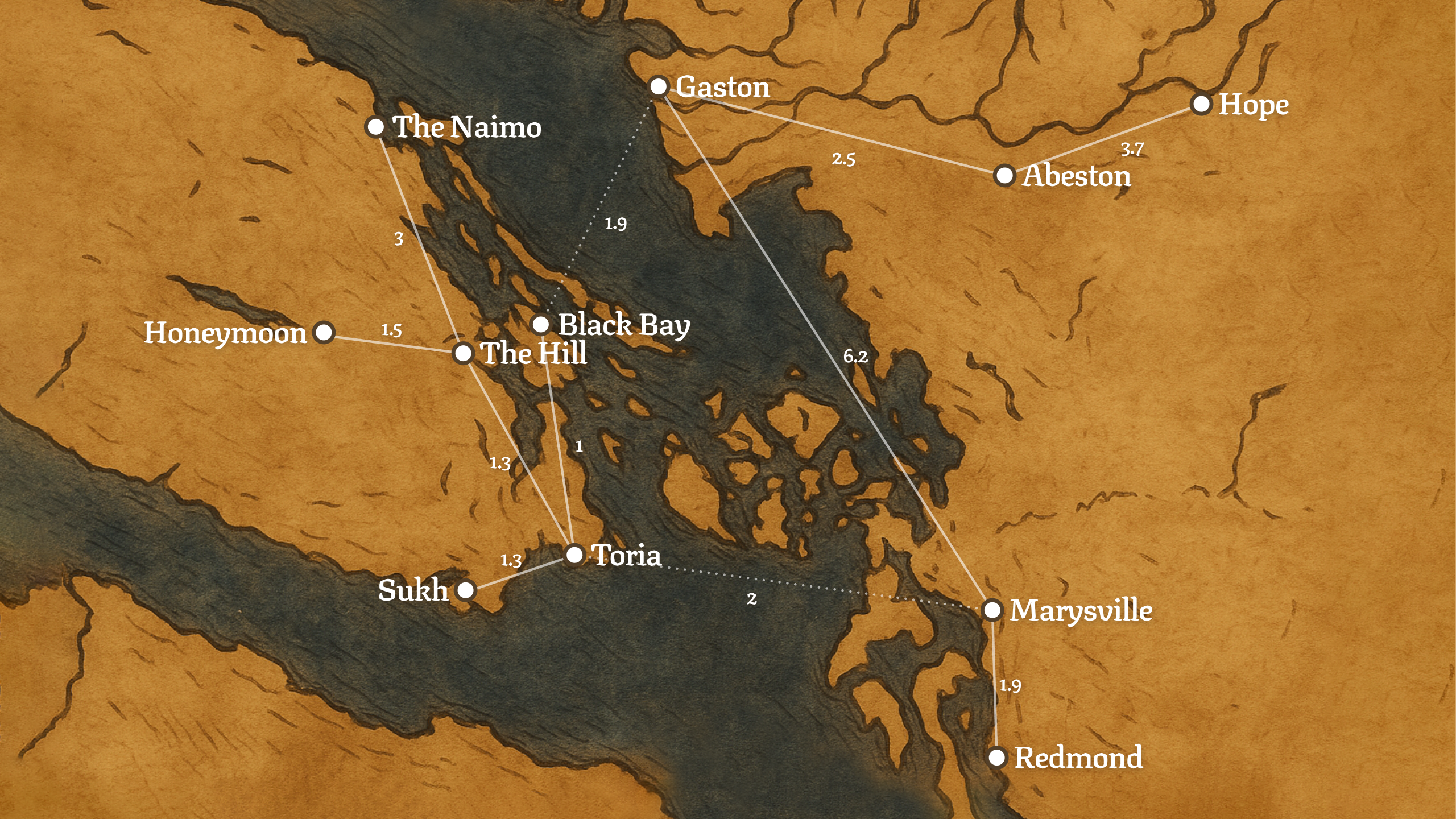

The days_travel can then help travelers choose how fast to travel. A number like 1.3 for the route from The Hill to Toria means either one hard day's travel, or two leisurely days of travel with camping outside for the one night. The bearing and distance fields make it easy to make itineraries with better visuals, and other fields can be used to show the difficulty of the route. Here is an example of what one of them might look like, superimposed over the geography of today's Vancouver Island.

Using WHERE to filter arrays

This sort of graph query that returns all the names of towns connected to The Hill is quite familiar to us by now.

We were able to filter using WHERE on the towns, but is there a way to filter from the next_routes result so that for example only a single town is returned?

Indeed there is. In the same way that we can use [] to index an array, we can also use it with a WHERE clause to filter them. Here is a quick example:

You can filter as many times as you want in a single statement, and even split it over multiple lines for better readability.

If the items in the array have named fields, you can refer to those fields instead of using $this:

Typing $this.temperature would have worked too.

This can be combined with a graph query to check to see if a planned route is valid and where to go next. The following query would be helpful for a traveler from The Hill who wants to go to Toria, but hasn't decided where to go next.

This can be extended as far as we like. For the traveler looking to go from The Hill all the way to Hope, we can follow the graph relations all the way to the end to make sure that the route exists, as well as to find some information for the traveler at the end. The output is a bit bland because we don't have much info about Hope, but in Aeon's time each town record probably has a lot more information than this.

Getting the shortest path in a recursive query

Aeon was given some good news in SurrealDB 2.2, which added three convenient algorithms for recursive queries that includes finding the shortest path from one record to another!

Now, since Aeon lives in the future it is technically true that SurrealDB 2.2 would have already been released by then, but we were unable to write about it until the functionality was created in the present time. This is one of those time paradoxes that you often see when the present and the future combine.

In any case, let's take a look at this syntax and how it can help. We will begin with a simple recursive query that follows the ->to->town path twice starting from the town of Toria, and then returns the name field from the towns it finds. In this dataset, the ID for Toria is town:g36e1zorb1ijxqzw2y67 so we can also use that directly.

The problem with this query is that the ->to path can go both ways, because if there is a ->to path from Toria to The Naimo, then there will also be a path from The Naimo to Toria. The output simply shows all the possible places you could be if you followed two paths. That's not very helpful!

We can fix this by adding +path to the recursive part of the query. Let's give that a try.

Not bad! At least now we can see what the actual path is to reach the final destination after two stops.

We can also add +inclusive to this if we want to include the original record, the one for Toria. Let's do that.

The output is the same as before, except that it's now clear that each of these paths all start at the town of Toria.

Now, what people are probably most interested in when using this map service is the shortest path. Fortunately, there is another keyword we can use here called +shortest=. The part after the = is the record ID that we want to get the shortest path to. It can also be a parameter that is a record ID.

Let's give this a try to see the shortest path from Toria to Edmond's Field, the city located the greatest number of trips away all the way across the mountains.

There is a third algorithm called +collect which collects all the records along the path. We can give this a try with .{4+collect} in the recursive part of the query to return all of the possible places you could be after taking four trips from Toria (including trips that go back to Toria, since ->to-> goes in both directions).

You can think of this as a list of places that can be reached within two or three days when starting from Toria.

We are pretty good at SurrealDB's geo functions and graph queries by now, so it's now time to move on to the next chapter to see what else Aeon and the team have in store. What other quality of life changes are coming to the world?

Practice time

1. How would you define a function that takes two strings representing Record IDs and uses them to create a relation?

Let's say that the function should be called fn::set_writer() and is used to insert an author and the ID of a book that the author has written.

Answer

There are many ways to do this, but two quick casts into a <record<person>> and <record<book>> inside of a RELATE statement is probably the shortest.

An INSERT RELATION could be an option too, since it can be written over multiple lines for readability.

2. How could you improve the error messages given when using the function?

Assuming that we are working with the following schema that requires wrote to go from a record person to a record book:

The original messages are fairly good, but could they be improved?

Hint

SurrealDB has a function that lets you check whether a string is a properly formatted Record ID or not.

Answer

Here is one way to do it, with a single error message for each parameter if the input is incorrect:

Here are two examples of the new error output:

You could try making the errors even more precise if you like. For example, you could first return an error message if the string::is_record() method fails, and then uses the record::tb() to check the table name of the record.

3. How would you write a function that takes an array of strings that represent a person and all of the person's direct ancestors and relates them?

Here is an example of the function in action. It should establish that Philip II is the parent of Alexander the Great, that Amyntas III is the parent of Philip II, and so on. To make it simple, we'll assume that all of these people are already in the database but aren't related to each other yet.

Hint

SurrealDB has an array function that makes it easy to slide one index at a time down an array.

Answer

The array::windows() function can help here. You can pass in the array as well as the number 2 to instruct it to return a sliding window of two items at a time: Alexander to Philip, then Philip to Amyntas, and so on.

With this function it's now easy to move from one parent-child pair down the entire list.

Finally, let's see who the parent of each person is.

4. You have an array of objects with some bad data and need to quickly filter out the bad data. How can you do it?

The array of objects looks like the data below, in which sometimes age is set to a string that doesn't parse into a number, and sometimes doesn't include a name. How would you filter out everything unless the object has a proper age field and a name?

Answer

You can use an array filter at the end with two requirements: that name IS NOT NONE and that age.is_number().

5. What could you define a literal to match an error type defined on someone else's software?

Here is an example of a possible error type in some other programming language that holds some data inside each possible error.

Answer

A literal could be a good option here. You could define it on a field to match the original code pretty closely, as follows:

After this, you could use IF ELSE statements to see if the first field in the error field is InvalidRole or NotAllowed. Here is a simple check of this type inside a function that takes a single record that holds this error data, and creates a separate record to show that the match has worked.

We can follow this up with two sample data records...

And then three queries to show that the error handling worked.