Using SurrealDB as a Vector Database

A vector database is specialized for storing high-dimensional vectors and for efficiently performing queries on them. Rather than searching on exact values or text-based queries, vector databases let you search based on semantic similarity. For instance, in a text embedding scenario, you can find documents that are semantically similar to a given query, even if they do not share the same keywords.

This allows for usage in areas such as:

- Recommendation systems: Suggest items (movies, products, etc.) similar to what a user has liked based on learned embeddings.

- Image or audio search: Identify images or audio clips semantically similar to a given sample.

- Clustering and classification: Perform unsupervised clustering of data points or quickly identify which category a vector is close to.

With SurrealDB’s SurrealQL you can define vector fields, store numeric arrays as embeddings, create indexes, and perform similarity queries. SurrealDB’s approach unifies these features to allow you to move from multiple data stores (a dedicated vector database plus separate document database and finally a graph database to stitch them together) to a single source of truth.

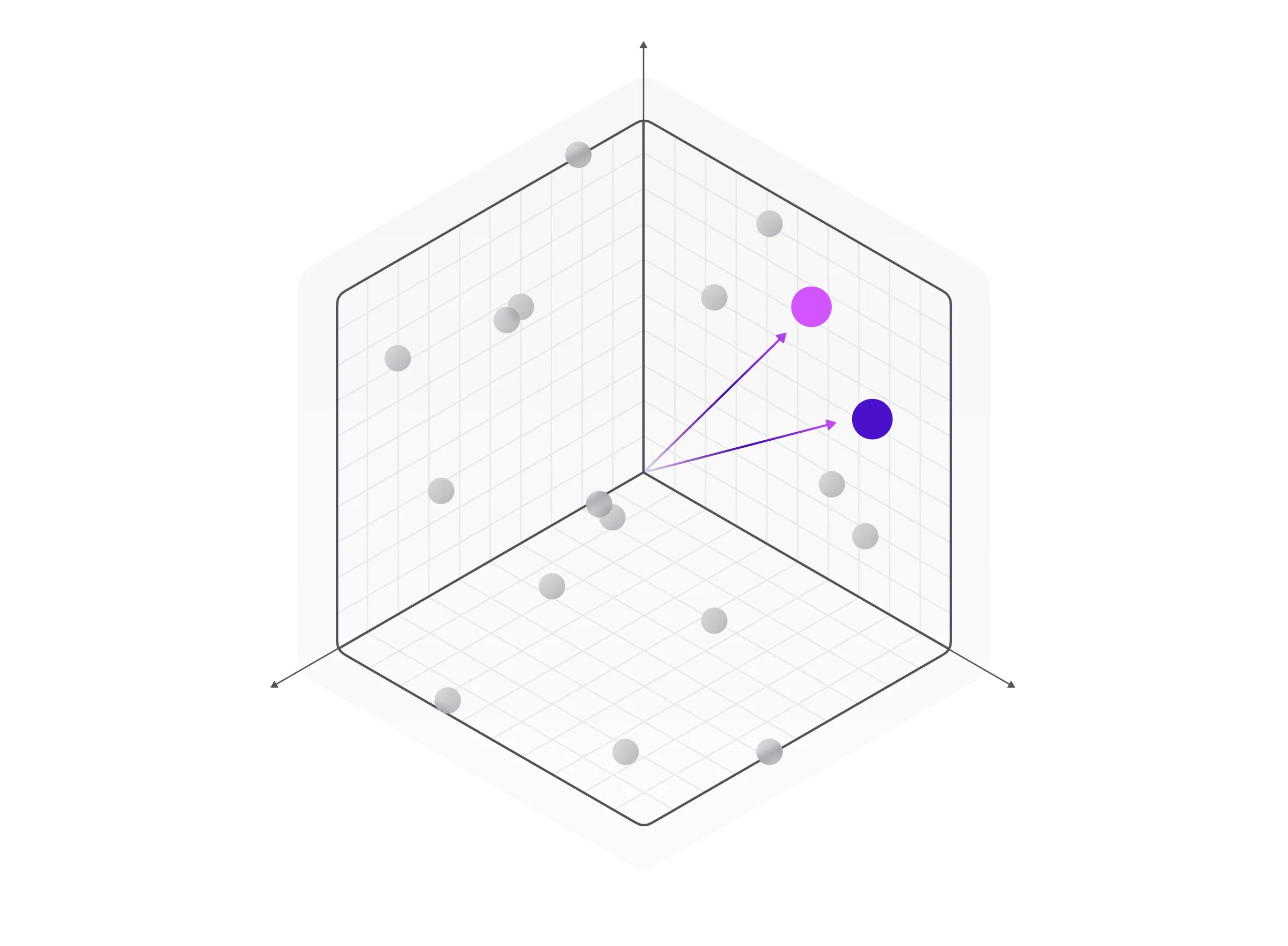

But how do you “think” in a vector database? Unlike relational or document models, where the focus is on well-defined schemas and relationships, vector databases revolve around embeddings—numerical representations of objects (like text, images, audio snippets, etc.) in a continuous vector space. This allows you to design data structures and queries to exploit these embeddings for similarity search or AI-driven retrieval.

Core concepts of vector-oriented modeling

Vector search is a search mechanism that goes beyond traditional keyword matching and text-based search methods to capture deeper characteristics and similarities between data.

Vector search isn’t new to the world of data science. Gerard Salton, known as the Father of Information Retrieval, introduced the Vector Space Model, cosine similarity, and TF-IDF for information retrieval around 1960.

It converts data such as text, images, or sounds into numerical vectors, called vector embeddings. You can think of vector embeddings as cells. In the same way that cells form the basic structural and biological unit of all known living organisms, vector embeddings serve as the basic units of data representation in vector search.

In practice, embeddings are typically dense vectors of real numbers that capture the semantic or contextual meaning of data. For instance, in Natural Language Processing (NLP), a word or sentence can be transformed into a vector of length 128, 256, 768, or even more dimensions. The idea is that similar objects (in meaning) end up having similar vector representations, making it possible to compute how close they are in the vector space.

Embeddings themselves are not generated by the database. Instead, they depend on which model is used to generate them. Various companies such as OpenAI and Mistral have both free and paid models, while many other free models exist to generate embeddings.

Inside a database they will be stored in this sort of manner.

[

{

embedding: [

0.0007022718782536685,

0.004178352188318968,

0.009888353757560253,

],

text: "To be, or not to be: that is the question."

},

{

embedding: [

-0.027426932007074356,

0.0008020889363251626,

-0.02949262224137783

],

text: "All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players."

},

{

embedding: [

-0.05859993398189545,

-0.011999601498246193,

-0.06185592710971832

],

text: "The course of true love never did run smooth."

}

]

To store vectors in SurrealDB, you typically define a field within your data schema dedicated to holding the vector data. These vectors represent space data points and can be used for various applications, from recommendation systems to image recognition. Below is an example of how to create records with vector embeddings:

CREATE Document:1 CONTENT {

items: [

{

content: "apple",

embedding: [0.00995, -0.02680, -0.01881, -0.08697]

}

]

};

There are no strict rules or limitations regarding the length of the embeddings, and they can be as large as needed. Just keep in mind that larger embeddings lead to more data to process and that can affect performance and query times based on your physical hardware.

In fact, embeddings retrieved from a model can be cut down to any length you prefer if the accuracy is still acceptable for your use case.

Vector search vs full-text search

SurrealDB supports full-text search and Vector Search. Full-text search (FTS) involves indexing documents using an FTS index that makes use of an analyzer that breaks down text using tokenizers and filters.

The image above is a Google search for the word “lead”, a word with more than one definition (and pronunciation!). Lead can mean ‘taking initiative’, as well as the chemical element with the symbol ‘Pb’.

Let’s consider this in the context of a database of liquid samples which note down harmful chemicals that are found in them.

In the example below, we have a table called liquids with a sample field and a content field. Next, we can doefine a full-text index on the content field by first defining an analyzer called liquid_analyzer. We can then define an index on the content field in the liquid table and set our custom analyzer (liquid_analyzer)to search through the index.

Then, using the select statement to retrieve all the samples containing the chemical lead will also bring up samples that mention the word lead.

If you read through the content of the tap water sample, you’ll notice that it does not contain any lead in it but it has the mention of the word lead under “The team lead by Dr. Rose…” which means that the team was guided by Dr. Rose.

The search pulled up both the records although the tap water sample had no lead in it. This example shows us that while full-text search does a great job at matching query terms with indexed documents, on its own it may not be the best solution for use cases where the query terms have deeper context and scope for ambiguity.

Vector search in SurrealDB

The vector search feature of SurrealDB will help you do more and dig deeper into your data. This can be used in place of, or together with full-text search.

For example, still using the same liquids table, you can store the chemical composition of the liquid samples in a vector format.

INSERT INTO liquidsVector [

{

sample:'Sea water',

content: 'The sea water contains some amount of lead',

embedding: [0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4] },

{

sample:'Tap water',

content: 'The team lead by Dr. Rose found out that the tap water in was potable',

embedding:[1.0, 0.1, 0.4, 0.3]

},

{

sample:'Sewage water',

content: 'High amounts of a were found in Sewage water',

embedding : [0.4, 0.3, 0.2, 0.1]

}

];

Notice that we have added an embedding field to the table. This field will store the vector embeddings of the content field so we can perform vector searches on it.

In the example above you can see that the results are more accurate. The search pulled up only the results in which the word “lead” was used to mean the material, while the final liquidsVector record had the lowest score. This is the advantage of using vector search over full-text search.

Another use case for vector search is in the field of facial recognition. For example, if you wanted to search for an actor or actress who looked like you from an extensive dataset of movie artists, you would first use an LLM model to convert the artist’s images and details into vector embeddings and then use SurrealQL to find the artist with the most resemblance to your face vector embeddings. The more characteristics you decide to include in your vector embeddings, the higher the dimensionality of your vector will be, potentially improving the accuracy of the matches but also increasing the complexity of the vector search.

Computation on vectors: “vector::” package of functions

SurrealDB provides vector functions for most of the major numerical computations done on vectors. They include functions for element-wise addition, division and even normalisation.

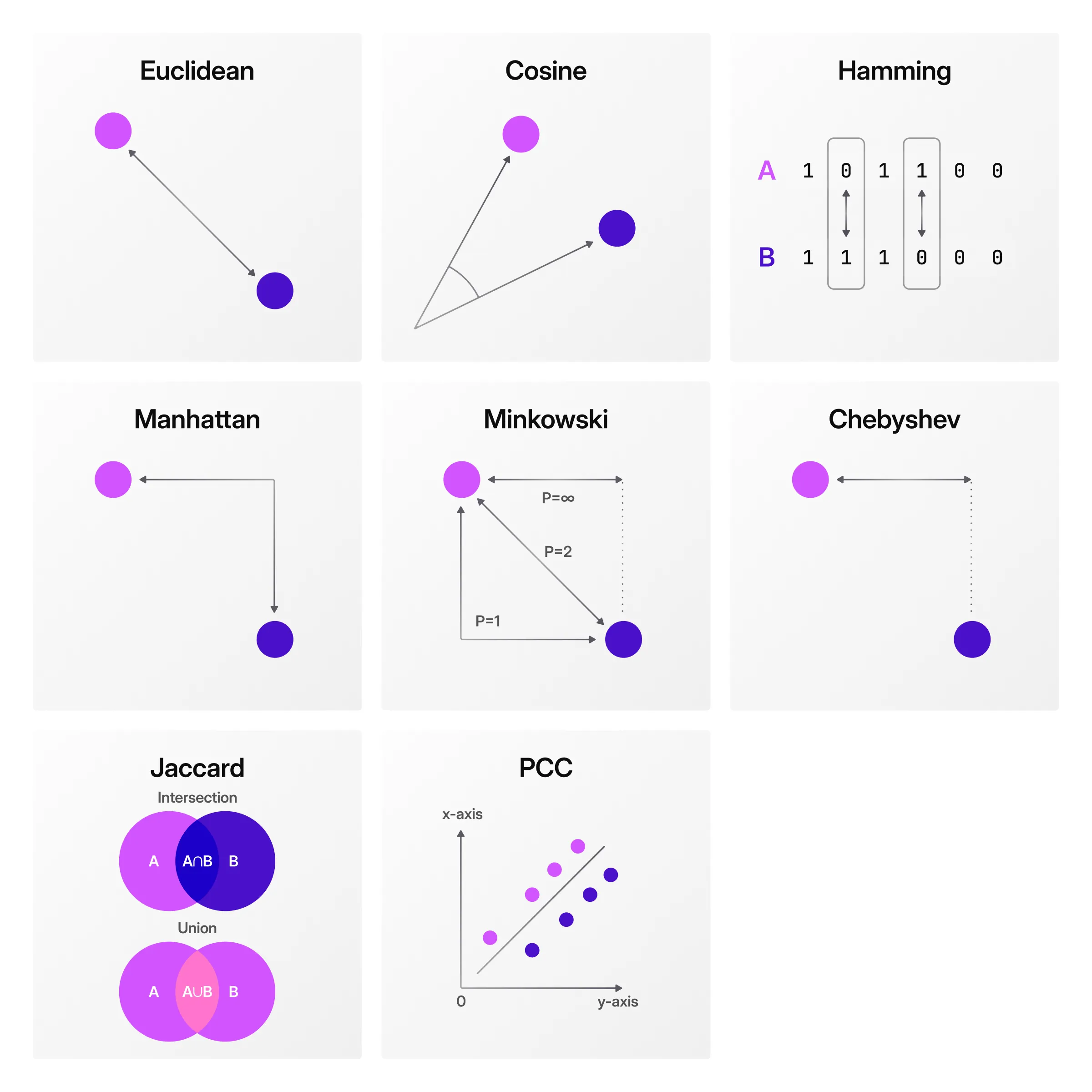

They also include similarity and distance functions, which help in understanding how similar or dissimilar two vectors are. Usually, the vector with the smallest distance or the largest cosine similarity value (closest to 1) is deemed the most similar to the item you are trying to search for.

The choice of distance or similarity function depends on the nature of your data and the specific requirements of your application.

In the liquids examples, we assumed that the embeddings represented the harmfulness of lead (as a substance). We used the vector::similarity::cosine function because cosine similarity is typically preferred when absolute distances are less important, but proportions and direction matter more.

Vector Indexes

When it comes to search, you can always use brute force.

In SurrealDB, you can use the brute force approach to search through your vector embeddings and data.

Brute force search compares a query vector against all vectors in the dataset to find the closest match. As this is a brute-force approach, you do not create an index for this approach.

The brute force approach for finding the nearest neighbour is generally preferred in the following use cases:

- Small datasets / limited query vectors: For applications with small datasets, the overhead of building and maintaining an index might outweigh its benefits. In such cases, the brute force approach is optimal.

- Guaranteed accuracy: Since the brute force method compares the query vector against every vector in the dataset, it guarantees finding the exact nearest vectors based on the chosen distance metric (like Euclidean, Manhattan, etc.).

- Benchmarking models: The brute force approach can be used as a reference to help benchmark the performance of other approximate alternatives like HNSW.

While brute force can give you exact results, it’s computationally expensive for large datasets.

In most cases, you do not need a 100% exact match, and you can give it up for faster, high-dimensional searches to find the approximate nearest neighbour to a query vector.

This is where Vector indexes come in.

In SurrealDB, you can perform a vector search using a Hierarchical Navigable Small World (HNSW) index, a state-of-the-art algorithm for approximate nearest neighbour search in high-dimensional spaces. It is a proximity graph-based index that offers a balance between search efficiency and accuracy.

By design, HNSW currently operates as an “in-memory” structure. Introducing persistence to this feature, while beneficial for retaining index states, is an ongoing area of development. Our goal is to balance the speed of data ingestion with the advantages of persistence.

You can also use the REBUILD statement, which allows for the manual rebuilding of indexes as needed. This approach ensures that while we explore persistence options, we maintain the optimal performance that users expect from HNSW, providing flexibility and control over the indexing process.

Filtering through vector search

The vector::distance::knn() function from SurrealDB returns the distance computed between vectors by the KNN operator. This operator can be used to avoid recomputation of the distance in every select query.

Consider a scenario where you’re searching for actors who look like you but they should have won an Oscar. You set a flag, which is true for actors who’ve won the golden trophy.

Let’s create a dataset of actors and define an HNSW index on the embeddings field.

CREATE actor:1 SET name = 'Actor 1', embedding = [0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4], flag = true;

CREATE actor:2 SET name = 'Actor 2', embedding = [0.2, 0.1, 0.4, 0.3], flag = false;

CREATE actor:3 SET name = 'Actor 3', embedding = [0.4, 0.3, 0.2, 0.1], flag = true;

CREATE actor:4 SET name = 'Actor 4', embedding = [0.3, 0.4, 0.1, 0.2], flag = true;

LET $person_embedding = [0.15, 0.25, 0.35, 0.45];

DEFINE INDEX hnsw_pts ON actor FIELDS embedding HNSW DIMENSION 4;

SELECT id, flag, vector::distance::knn() AS distance FROM actor WHERE flag = true AND embedding <|2,40|> $person_embedding ORDER BY distance;

[

[

{

distance: 0.09999999999999998f,

flag: true,

id: actor:1

},

{

distance: 0.412310562561766f,

flag: true,

id: actor:4

}

]

];

actor:1 and actor:2 have the closest resemblance with your query vector and also have won an Oscar.

Hybrid search functions

As mentioned above, full-text search and vector search can both be used in SurrealDB. In addition, some functions exist inside the search:: that take both full-text and vector arguments in order to produce a single unified output.

Here is an example of one of them called search::rrf() which does this using an algorithm called reciprocal rank fusion.

CREATE test:1 SET text = "Graph databases are great.", embedding = [0.10, 0.20, 0.30];

CREATE test:2 SET text = "Relational databases store tables.", embedding = [0.05, 0.10, 0.00];

CREATE test:3 SET text = "This document mentions graphs.", embedding = [0.20, 0.10, 0.25];

DEFINE ANALYZER simple TOKENIZERS class, punct FILTERS lowercase, ascii;

DEFINE INDEX idx_text ON TABLE test FIELDS text FULLTEXT ANALYZER simple BM25;

DEFINE INDEX idx_embedding ON TABLE test FIELDS embedding HNSW DIMENSION 3 DIST COSINE;

LET $qvec = [0.12, 0.18, 0.27];

LET $vs = SELECT id FROM test WHERE embedding <|2,100|> $qvec;

LET $ft = SELECT id, search::score(1) as score FROM test

WHERE text @1@ 'graph' ORDER BY score DESC LIMIT 2;

search::rrf([$vs, $ft], 2, 60);

Vector search cheat sheet

- HNSW: efficient approximation for high dimensions or large datasets

- Brute force: when you don’t define an index, or you want exact nearest neighbours, or when you provide a distance function to the query

HNSW Index

| Parameter | Default | Options | Description |

|---|

| DIMENSION | | | Size of the vector |

| DIST | EUCLIDEAN | EUCLIDEAN, COSINE, MANHATTAN | Distance function |

| TYPE | F64 | F64, F32, I64, I32, I16 | Vector type |

| EFC | 150 | | EF construction |

| M | 12 | | Max connections per element |

| M0 | 24 | | Max connections in the lowest layer |

| LM | 0.40242960438184466f | | Multiplier for level generation. This value is automatically calculated with a value considered as optimal. |

Examples:

DEFINE INDEX hnsw_idx ON pts FIELDS point HNSW DIMENSION 4;

DEFINE INDEX hnsw_idx ON pts FIELDS point HNSW DIMENSION 4 DIST EUCLIDEAN TYPE F64 EFC 150 M 12 M0 24 LM 0.40242960438184466f;

For more details, see the DEFINE INDEX statement documentation.

Querying

DEFINE INDEX hnsw_idx ON pts FIELDS point HNSW DIMENSION 4;

LET $vector = [2,3,4];

SELECT

id,

vector::distance::knn() as dist

FROM pts

WHERE point

<|2|>

$vector;

| SELECT Functions | |

|---|

vector::distance::knn() | reuses the value computed during the query |

vector::distance::chebyshev(point, $vector) | |

vector::distance::euclidean(point, $vector) | |

vector::distance::hamming(point, $vector) | |

vector::distance::manhattan(point, $vector) | |

vector::distance::minkowski(point, $vector, 3) | third param is 𝑝 |

vector::similarity::cosine(point, $vector) | |

vector::similarity::jaccard(point, $vector) | |

vector::similarity::pearson(point, $vector) | |

WHERE statement

| Query | HNSW index |

|---|

<|2|> | uses distance function defined in index |

<|2, EUCLIDEAN|> | brute force methood |

<|2, COSINE|> | brute force method |

<|2, MANHATTAN|> | brute force method |

<|2, MINKOWSKI, 3|> | brute force method (third param is 𝑝) |

<|2, CHEBYSHEV|> | brute force method |

<|2, HAMMING|> | brute force method |

<|2, 10|> | second param is effort* |

*effort: Tells HNSW how far to go in trying to find the exact response. HNSW is approximate, and may miss some vectors.

Notes

- Verify index utilization in queries using the

EXPLAIN FULL clause. E.g: SELECT id FROM pts WHERE point <|10|> [2,3,4,5] EXPLAIN FULL; - 𝑝 values: (more about 𝑝 in Minkowski distance)

- 20 = 1 → manhattan/diamond ◇

- 21 = 2 → euclidean/circle ○

- 22 = 4 → squircle ▢

- 2∞ = ∞ → square □

Conclusion

Vector search does not need to be complicated and overwhelming. Once you have your embeddings available, you can try out different vector functions in combination with your query vector to see what works best for your use case. As discussed in the reference guide, you have 3 options to perform Vector Search in SurrealDB. Based on the complexity of your data and accuracy expectations, you can choose between them. You can design your select statements to query your search results along with filters and conditions. In order to avoid recalculation of the KNN distance for every single query, you also have the vector::distance::knn().

Due to GenAI, most applications today deal with intricate data with layered meanings and characteristics. Vector search plays a big role in analyzing such data to find what you’re looking for or to make informed decisions.

You can start using vector search in SurrealDB by installing SurrealDB on your machines or by using Surrealist. And if you’re looking for a quick video explaining Vector Search, check out our YouTube channel.

If you’re interested in understanding Vector search in depth, checkout this academic paper on Vector Retrieval written by Sebastian Bruch.

Resources