I shot the sheriff. But I swear it was in self-defence.

Bob Marley

Hi there! Welcome to our guide into the world of knowledge graphs. This document is for you if:

you are an engineer working in gen AI

you want to understand why knowledge graphs are relevant for AI agents

Introduction

Let’s start by placing knowledge graphs on the map, by showing a modern multi-agent RAG architecture. In this example, assume each agent has a different role in the process to answer a user's prompt. In order to make this happen, each agent comes equipped with its own tool or tools like web search, MCP servers, and more. A knowledge graph in this case is just another toolset for the agents.

I’m using the word “tool” very casually, but tool calling is a very important concept in our context. Most modern LLM models (like Claude Sonnet 4.5, Gemini 3 Flash Preview, DeepSeek V3.2, and more) are capable of using tools as part of their process before generating an answer. These tools can be built in the model (like web search in Claude models) or provided by you (like the example below).

This Python code shows how you can provide your agent with a “retrieval” tool from your knowledge graph. The docstring in this function gives to the LLM the information it needs to know when and how to call this function.

While this blog post is full of SurrealQL example code, I actually passed over the SurrealQL query in the above example that does the actual search on the knowledge graph. That's because it deserves its own blog post, which I promise to cover in Part 2 of this series: “Navigating a knowledge graph”.

Before diving into how to build a knowledge graph, let’s define what they are.

What is a knowledge graph?

In knowledge representation and reasoning, a knowledge graph is a knowledge base that uses a graph-structured data model or topology to represent and operate on data. Knowledge graphs are often used to store interlinked descriptions of entities - objects, events, situations or abstract concepts - while also encoding the free-form semantics or relationships underlying these entities.

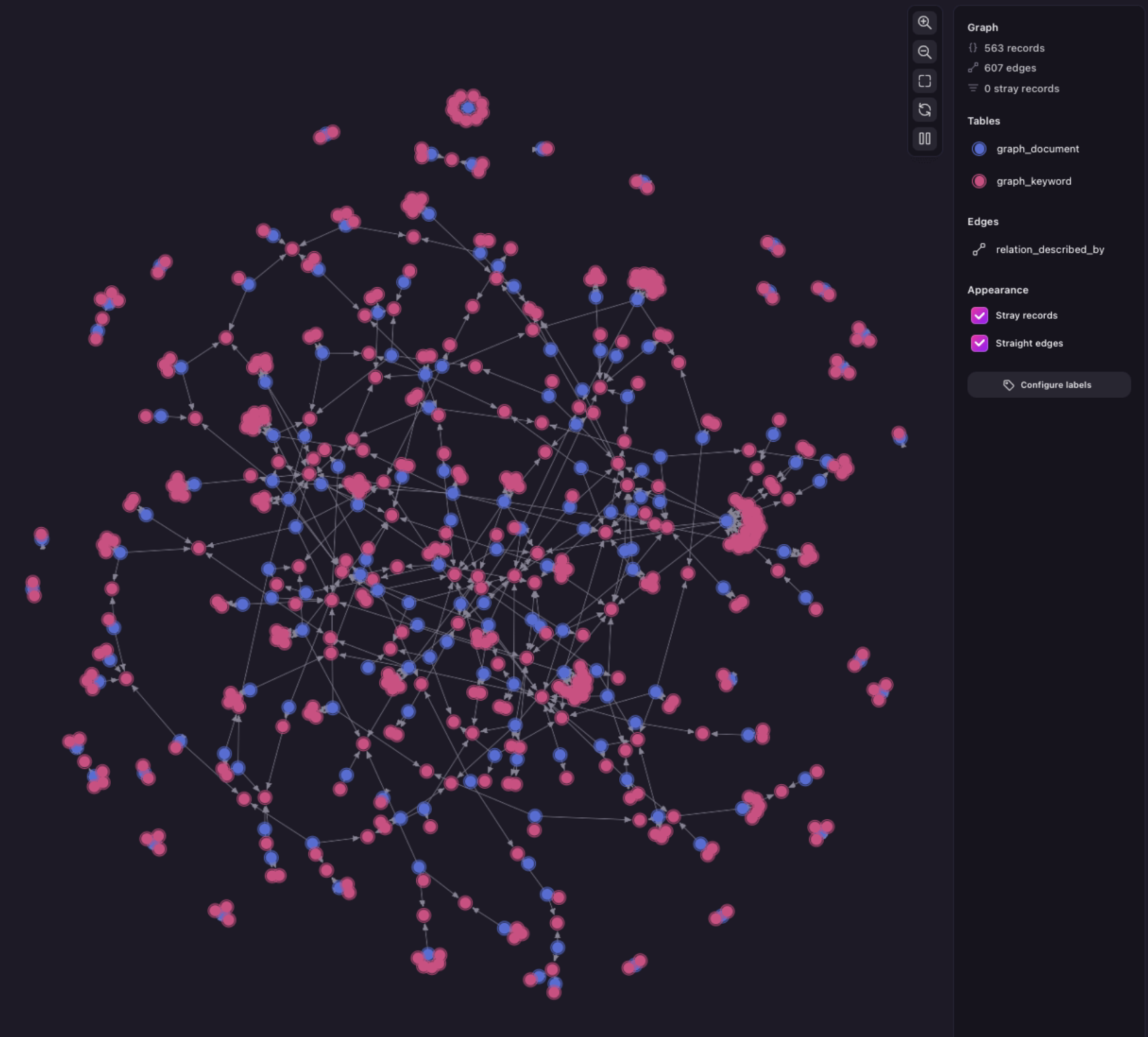

Here in the image below I present two specimens of a knowledge graph. The first one is a very structured and predictable one, whose nodes and edges are explicit in the original data. The second one is its opposite: a more free-form graph, with some entities inferred by an LLM out of the corpus.

If you take a close look you'll see that's why the first one includes only a single prepared graph edge called INCLUDES, while the second has more than one such as MENTIONED_IN and PUBLISHED_IN - these were generated by the LLM which concluded it made sense to use these to describe the relation between entities.

But… 🤔

When do AI agents need a knowledge graph?

Because LLMs by themselves are brilliant storytellers but with a fuzzy memory. In turn, AI agents are designed to perform tasks and make decisions, requiring the accuracy only a structured graph can provide. An LLM with a knowledge graph is like a storyteller with a highly-organised, cross-referenced encyclopedia.

Example to show some of the benefits:

“Summarise the reviews of this month’s most popular product in our store”

With a prompt like that, and a knowledge graph like in the example before, your agent would be able to deterministically retrieve the list of the reviews for the best selling products. Let's see how easy this is to do with a SurrealQL query.

The output of this last query will look like this.

Want to give it a try yourself? Head on over to the online Surrealist UI, go into the sandbox and run the following statements to set up the schema and seed data before running the query we just saw.

And to finish up this example, here is a bonus query that lets you see all incoming graph edges to a table. The ? here is used as a wildcard to match anything, which in this case means all of the product_in_order and review_for_product edges in between the order and review tables.

We can use this data to explain the main benefits of a knowledge graph:

multi-hop reasoning: it navigates the graph to one or more edges:

review → review_for_product → product → product_in_order → orderdeterministic accuracy: the query output is backed by hard data, a fact that will add great value to the LLM context.

explainability: if required, besides the plain answer, you get the query that was executed and the structured results. In our example, you get the list of reviews, but also which is the top-selling product, and if you wish, you could include how many items were sold.

reduced hallucinations: because we leveraged our graph relations to exactly know which are the reviews of the best-selling products, the LLM just needs to summarise them. That leaves little room for hallucinations. Compare this to asking the same question with RAG on ingested sales reports instead of a knowledge graph: the data about which is the best selling product may or may not be mentioned in one of those documents, which will get retrieved using semantic search (or at least a chunk of the report), and fingers crossed, that chunk gets a good enough score to be picked up and included into the LLM context.

dynamic knowledge: whenever new orders and reviews are created, the query will pick them up. Because of its structured nature, it’s easier to keep up to date, specially if your “transactional” DB is the same as your knowledge graph DB.

When is a knowledge graph not necessary?

As a counterexample, let's look at another use case in which a knowledge graph might be overkill:

Dataset: successful troubleshooting conversations with customers (from support ticket system or e-mail), internal support conversations from company chat (e.g. Slack threads), FAQs and documentations from internal wiki (e.g. Notion, PDFs, etc.)

Agent job: answer questions like: “Robot firmware is v.1.67 and I can’t get access via SSH”

A vector store populated with the available dataset may provide good references for an LLM to help.

You should only consider adding graph relations to the mix if your vector store is too big, or you have very dense neighbourhoods (e.g. a lot of troubleshooting chats about the same issue, causing context distraction, confusion, and clash). You might also want to trim down the vector space by relating chunks to specific domains (support category, product line, firmware version).

This image illustrates dense neighbourhoods, and how graph relations can help to trim down the vector space, by running queries that read like this: “find reviews in the proximity of $vector AND are connected with ->review_for_product->product->product_in_category->dragons”.

Moving from unstructured data to a knowledge graph

These are the main steps that are required to go from unstructured data to having a knowledge graph for your AI agents. The Extraction, Transformation, and Loading steps are commonly referred to as ETL.

1. Extraction

1.1. Parsing

For each document, parse it and transform it into structured data. It could be a CSV file which is already structured, but unstructured data like a PDF with text, images, and tables can be worked with as well.

1.2. Chunking

We now have “plain” data, which is commonly (but not necessarily) kept in Markdown format. It is very likely that the document may be too long, which is less than ideal for LLMs which have a finite context window (references: https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.05167).

1.3. Embedding

Semantic retrieval is possible because of vector embeddings. You decide what you want to embed. You almost always want to embed chunks, but can also embed content on graph nodes (e.g. to run a semantic search on keywords and from there query other connected nodes).

1.4. Entity and relationship extraction

Entities will become nodes (any concept like people, document, product), and relationship edges (any verb or predicate like works_at, explains).

Depending on your data, and how structured it is, some of the entities and relationships will be easy to extract because they may be explicit in the data (e.g. Martin → works_at → SurrealDB). Some others will require to be inferred based on some context (e.g. extract from a threads that Martin → knows_about → SurrealQL).

2. Transformation

This step in the process is meant to clean your data. Here are some ideas for what you might want to do at this point:

Deduplication and ontology alignment: for example, you might have Arnold → governor → California along with Schwarzenegger → star of → Predator.

ArnoldandSchwarzeneggershould get merged.Inference and enrichment: there are pros and cons about inferring attributes when generating a knowledge graph. It depends on your specific needs, but be careful: you could burn through tokens generating things that were never used, plus using inferred attributes as context could lead to inaccurate results. Inferred attributes work better as ways to navigate the graph, rather than to provide context to the LLM. As an example, take LightRAG, which demonstrates good results using “inference and enrichment” in a clever way to aid with navigation rather than context.

3. Loading

Loading is the last step in the ETL process. Here’s where you connect things with each other in the database, both vector embeddings, and graph relations. Look at the practical Loading example below.

Next, you’ll find common practices and practical examples for parsing, chunking, and all the steps mentioned above.

Practical examples

To finish up today's post, let's look at some examples of how to do the following:

Parsing unstructured data

The following example shows how to use Kreuzberg to parse PDFs. You may need to configure it differently, depending on your documents and the types of content. It’s not the same to parse a simple PDF, a PDF with images and tables, a spreadsheet, or websites.

For our example here, I use a flow decorator to register functions for different steps in the ETL process. An orchestrator takes care of calling this function for documents that lack a “stamp” in their chunked column:

The chunking_handler is in charge of the actual parsing. The code (simplified from kreuzberg_converter.py) looks like this:

A simple trick: hash the chunk and use that as the ID to avoid generating embeddings for chunks that already exist. This applies to mostly every record that gets processed in any way, not only for chunks.

Find the complete code in ingestion.py.

Resources:

Commercial solutions: Document AI from Tensorlake, https://www.datalab.to/

Chunking documents

Let’s use an example document to explain different chunking strategies, but be mindful that other use cases may favour different strategies. Imagine your “raw” documents as backups of group chats. They are plain text files, in which each line looks like “\{user\} \{timestamp\} \{message\}”.

Different strategies:

Token limit: chunks documents of equal size to guarantee that they fit into your embedding model window (commonly between 512 to 8k tokens)

Recursive: Instead of a hard cut at N characters, it uses a hierarchy of separators (typically ["\n\n", "\n", " ", ""]) to find the best place to split.

Semantic: chunks document based on their semantic meaning. With our group chat example, chunks are divided when the conversation topic changes.

Structure: Rather than treating a document as raw text, these strategies use the inherent formatting (Markdown, HTML, or Code) to define boundaries

Custom: be creative! Bringing our group chat example again, you can decide on periods of silence as a good point to split chunks. Doing this would be faster and cheaper than using the semantic strategy, and probably as accurate.

Simple and cheap strategies are worth trying first to have a good baseline. You then evaluate the results, and decide if a better (and more expensive) solution is required. This often produces better results than starting by choosing a complex strategy that may be overkill.

Another tip: adding overlaps to the chunks is a common practice, specially for the strategies that are simpler best-effort ones.

Embedding generation

Directly using provider SDKs:

With an AI framework, like pydantic-ai:

Entity and relationship extraction

This function shows how to extract concepts from a chunk, and relate them with graph edges:

The implementation of infer_concepts is a bit complex because it’s abstracting multiple providers. So, here is a simplification:

Using additional_instructions allows us to reuse then function infer_concepts for different domains.

Loading

For the following example, assume the following schema:

Vector indexes on: chunk and keyword tables

Graph relations: PART_OF, MENTIONED_IN

Tables: chunk, document, keyword

We have extracted the entities and relationships from the chunks, so we are ready to insert the nodes and edges into the graph, using semantic triplets like these:

chunk → PART_OF → document

keyword → MENTIONED_IN → chunk

In Python, it looks like this:

The code above is an simplification of inference.py from this knowledge-graph example, which uses utils functions (e.g. embed_and_insert) from our Kai G examples repository.

q(80)/d62cfitjoqgc73be5iv0.auto)

q(80)/d65ks6dhk7ec73f2k0dg.auto)

q(80)/d65ks6dhk7ec73f2k0d0.auto)

q(80)/d65ks6dhk7ec73f2k0e0.auto)

q(50)/d5svric8bm2s73cj5ks0.auto)

q(50)/d69e7l5hk7ec73f2kdbg.auto)